How Will Data Influence the Future of Machine Learning? — AI Show

October 16, 2018 in AI & Engineering

Share

In this blog post

Scott: Welcome to the AI Show. On the AI Show, we talk about all things AI. Today we have the question, our big question today:

How will data influence the future of machine learning?

Susan: You know, it's a pretty key thing, as we've discussed many times before.

Scott: Well, you have to have the trifecta, right?

You've got to have computing power,

You've got to have data,

You've got to have good models.

Susan: You know, I think we're starting to see some trends here.

How do normal machine learning problems go?

Scott: Well, if you have a small amount of data, then you use some simplistic models and things like that. If you have a large amount of data you probably will have to use a lot of computational power. But, also it can shape your model and make it more intricate, more nuanced. That's usually how that goes. But, it isn't necessarily that the bigger the data, the better your model is going to be, right?

Susan: No, definitely not. Data plays a key role, and the size of data definitely helps if you've got more, but there's a lot more that goes into it. But, we're starting to see a lot of these problems evolve along a standard path. We've seen this a couple times now.

Scott: How do they evolve?

Susan: It seems like there's a couple key points in the life of a machine-learning problem. At least, I've noticed this. Have you noticed this?

Scott: I, probably. I don't know. I'm not sure what you're thinking.

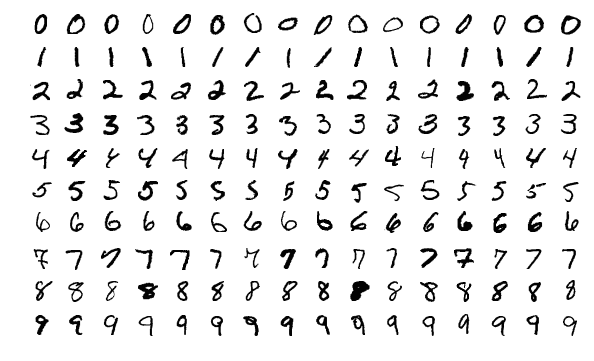

Susan: Well, here's what I'm thinking, I'll just lay it all out on the table right here. In general, we see a problem emerge, that people finally recognize as a problem. And I've noticed, and a lot of people have noticed, that pretty soon someone publishes a dataset. It becomes the dataset that everybody works their magic against to try to attack this problem the first time. Like, the classic - handwriting digits or image recognition. There's a lot of classic datasets that, once those were published, people could try different algorithms and compare them.

Scott: Yep. So if you're drawing "0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9," just writing it. "Hey, can you recognize those?" That type of dataset. Maybe another simple one like, "What category does this fall into? Is it a human? Is it an airplane? Is it a cat?"

Susan: Yeah, we've talked about CIFAR dataset and stuff like that. But, those standardized public datasets really help frame the problem. Then following that, you get some tools that will generally come out. We're seeing Tensorflow, PyTorch, all these standardized tools kind of follow along. But, people start standardizing: ImageNet and stuff like that. Like, "Hey, here's eight ways to attack this problem."

"We see the evolution of this problem go from understanding there's a problem, a classic dataset's released, a bunch of people and academic papers get published, some standardized solutions start coming out, and you see the polish on the solutions start evolving over time."

Scott: And the progress is rapid. You can look back and be like, "Wow, how did so much get accomplished?" But, it also still takes place over the span of decades. Like, MNIST, the hand written digits, was 20 years ago.

Susan: Maybe more.

Scott: Maybe a little longer. But yeah, CIFAR, probably a similar age, at least close, not quite as old. ImageNet, 10 years roughly, et cetera.

Susan: It's pretty cool to see that we've had enough of these problems that we can see those arcs going through them. From that we can see new problems and gauge where they're at. It's like charting a star: "This is how old it is based on how it looks."

Scott: That's a good point. That's sort of based on

How hard is the problem?

How easy is it to get the data?

How scintillating is the data?

Is it something that you can find for free easily on the Internet, nicely labeled?

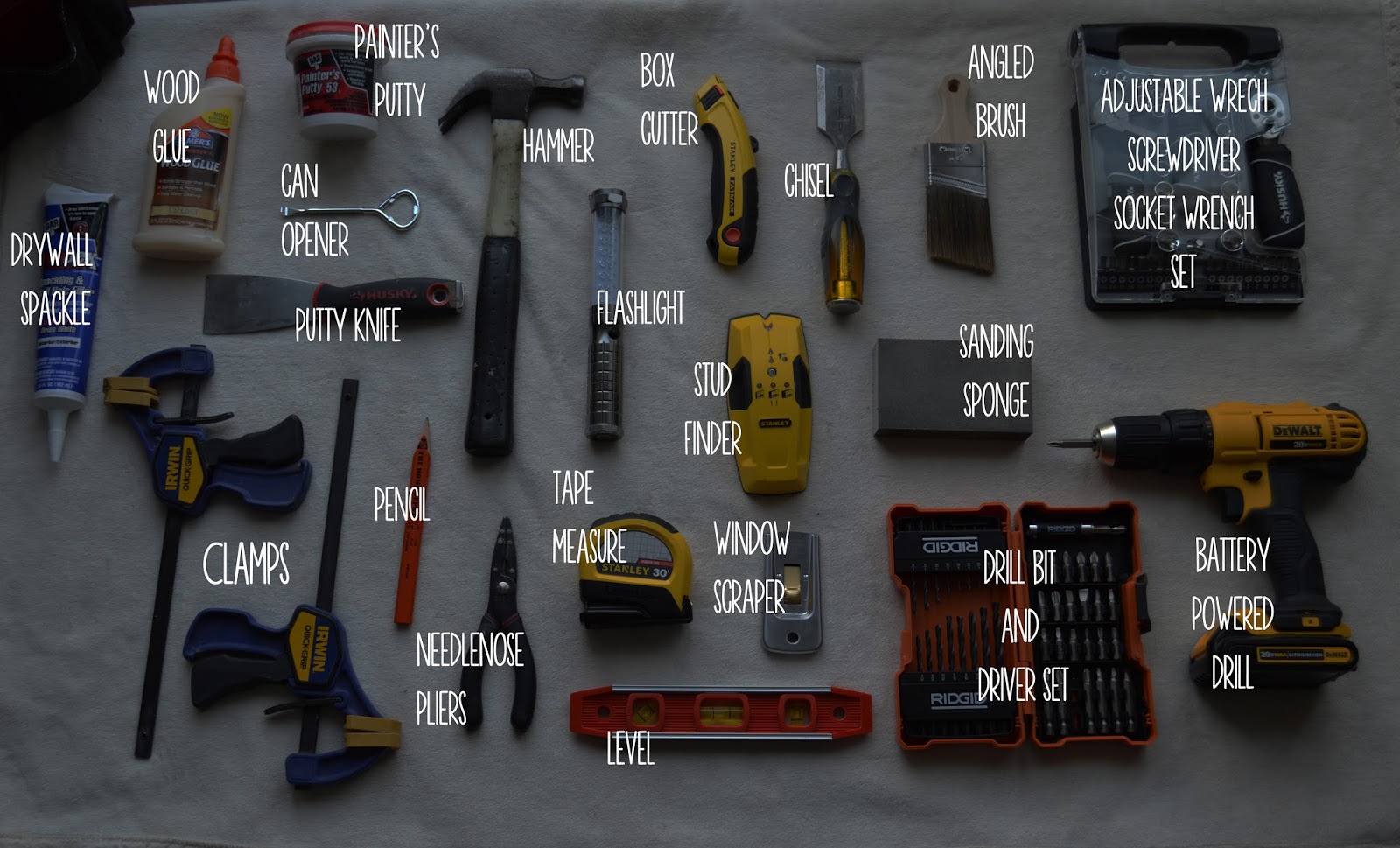

Images are like that a lot. It's easy to find a lot of images that are labeled. Not super easy, but you can search for a "tool" and you'll find tons of pictures of tools. Okay, that's pretty easy. But, there isn't an easy way for speech recognition to say the word, "tool." "Give me all the examples of everybody saying that word." That's a harder problem.

Susan: Well, by the time that becomes easy it probably means that the problem has been

Scott: Problem has been solved!

Susan: Which is the other cool thing. But it does bring up, as these problems have gotten tougher, they're still kind of following that arc.

Scott: Well, it's not trivial. The reason that you could search for a tool and get pictures of a tool is because people would label them.

Susan: Yes.

Scott: Here's the caption: "A picture of a tool."

"Oh, okay. So that probably means that's what the image is." But, that's not how it goes in audio. If you just recorded your meetings, you're not going to sit down and label all the moments.

Susan: No.

Scott: Not generally. Usually not.

Susan: There are more and more academic sources that are helping to do that. And, the problem is growing over time. But yeah, that is just hard.

To the viewers at home, if you want to appreciate how hard speech is, just say something in your own voice for five minutes and record it. Then transcribe what you said and see how long it takes.

Scott: Sit down, try to get it exactly. You already know what you're talking about. You already know all the vocabulary words.

Susan: You're the one who said it!

Scott: Yeah! You know your voice, right? And then you're like, "Wow, this takes a lot longer than I would expect."

How datasets come to be

Scott:

Is the data fairly easy to get?

Is it pretty freely available?

Is it all that hard to label?

Is it a problem that's worth solving or interesting to solve? You have to have all of those things, and then the datasets pop up.

Susan: There's one more angle here that's been popping up more and more lately. That, in the early datasets, we really just didn't concern ourselves with. That is the privacy angle of the dataset. As these tools are getting better and better, as we're putting more and more attention to them, and as the amount of data grows, even what you might think are trivial datasets become big privacy concerns.

You thought you were anonymizing your history here, and suddenly now everybody knows what movies you've been watching. Remember the Netflix prize?

Scott: Yeah, maybe eight years ago now? It was a machine-learning prize. It was, "Get a million dollars if you're able to make a recommendation that's better than 90% accurate," or something like that. Recommend movies to people. Then, if that matches the taste of something that they would like, that's how you gauge your accuracy. They ran that and a bunch of different academics and companies and whatnot went after that problem.

:format(webp)/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/49520055/netflix-prize1.0.jpg) Winners of the Netflix prize; photo: dannypeled.com

Winners of the Netflix prize; photo: dannypeled.com

Susan: It kind of did follow the same curve we were talking about earlier:

A big dataset was put out there

A bunch of different people, academics, started throwing a lot of different answers to it,

They finally got to an acceptable solution.

Now, from what I understand, the solution that won wasn't what they actually implemented, because it was a fairly complex, heavyweight thing and they wanted a more stripped down version of it. But, it does show that arc, and it also shows how privacy really came into this, because afterwards the security researchers got a hold of this dataset and they started linking real people back to these anonymized movie records.

Scott: It was like, can you guess, even with 30% accuracy or 10% accuracy, who this person is? Based on just the movies that they like.

The challenging link between data and privacy

Susan: This is a growing trend in these datasets and it also is a growing challenge. Because, like we said, when you publish those datasets, it helps frame the problem. But, if you're getting challenges publishing it because you've got privacy concerns, that could put the brakes on a lot of problems that might be solved. There's tradeoffs here. I'm not advocating throwing out privacy, let me be very clear about this.

Scott: In order to make AI work well, you need data. And, how do you get data? You get it from people. People say things, or people do things, or they take pictures of things, or they write things, or whatever. So laws surround the use of this data and it's been fairly free up until recent times. GDPR happened in Europe, and so that means that you have to very explicitly give permission to use your data, rather than it defaulting to being able to use the data. The US is still pretty free about this.

People are probably going to have to choose, in the future or now, in the next ensuing years, what do we want that to look like? Do I have to give you my data in order to use a very useful service, yes or no? Is there some other protection in there? How does that work? But the way that it'll probably work is that if you say, "No," then you probably are giving up some functionality there, because now it can't learn from you.

Susan: So one thing you and I have talked a lot about is a symbiotic evolution of these things. What you see is huge privacy concerns through big data breaches and things like that, you get a swing on the other side, privacy laws start coming in, which shapes the next set of concerns, which shapes the next set of laws.

This is what you see everywhere and honestly, we're kind of at the beginning of this. We're starting to really see big legal entities come in and move and start doing this, and they think they've got enough information to start building laws and stuff like that. This is the beginning of a process that's going to take decades to shake out. So it's a huge, huge, huge thing that you have to pay attention to when dealing with this.

Scott: This has been in the news recently with Apple, Tim Cook. Apple CEO Tim Cook at a data privacy conference giving a keynote there and sort of lampooning a lot of the other tech companies, saying, "Hey, you're stepping on people's data rights."

We believe that privacy is a fundamental human right. No matter what country you live in, that right should be protected in keeping with four essential principles:

Tim Cook (@tim_cook) October 24, 2018

Susan: Yeah, it's interesting to see a very large company, especially one with access to so much personal data.

Scott: With tons of data. With machine learning groups.

Susan: And moving into huge fields like personal health monitoring and stuff like that which they do a huge, huge amount of that.

<iframe width="560" height="315" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/wFTmQ27S7OQ?start=1206" frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture" allowfullscreen=""></iframe>

Scott: They've always planted a flag in the ground and said, "We are security conscious. We are data privacy conscious, et cetera," Apple has been.

Famously saying, "Hey, we're not going to give you the keys to unlock somebody who's been arrested's iPhone." Things like that.

Susan: I think they just shut down a major tool, with the last iOS 12 and above upgrade. So, they've been doing this but (this is the jaded side of me) I'm going to have to ...

Scott: You don't really believe it?

Susan: Well, I mean, it's kind of hard to see big companies saying that they're altruistic. I'm not saying Apple's evil or anything like that. I'm just saying you always have to take a grain of salt with a big company movement. That's a well thought out movement and they have, I'm sure, some under the hood ideas that they're not telling everybody.

Scott: And there's a competitive landscape that you're in as well. Hey, you're a company, other people are getting data, and maybe you are taking a stance so that you don't. Okay, now you have a competitive disadvantage.

Maybe this is why he's saying those things, so that competitors like Google, Facebook, et cetera, have more heat put on them from the government.

Susan: Also, if you come out early as an advocate, knowing that it's going to go down the route of tighter and stricter laws, maybe you have more influence. Maybe you can shape those laws more in your favor. Apple definitely would want to shape those laws in their favor, any big company is going to say, "Hey, make it work for me, as best as I can." So you come out waving the flag of privacy first, and you get a bit more of a voice and that's inevitable.

Scott: Sure. You want to build a company, or you want to build products, that people aren't going to hate, they're going to like, they're going to want to keep using, and they provide value. You just have to find that balance. Apple will have to find that balance. Every company will have to find that balance. With data and the models that they build.

Susan: It's true. But it is interesting, again, going back to the general theme here, seeing the arc of these problems, and seeing that simple arc is getting more and more complex by the day. But that complexity is also growing.

Scott: Understandably.

Susan: Understandably. And the complexity is growing with the complexity of the problems we're tackling. When we first wanted to figure out, is this a 1 or a 7? Is this a horse or a pig? When they first came out, they were incredibly hard problems to solve. Now it's like, "Yeah, of course that's easy." We're tackling really deep, hard problems now.

Another great dataset that just came out, Twitter.

Scott: Text datasets, Twitter.

Susan: That's a big one. It hits all of these fronts. This is talking about really complex social issues and really complex technological issues all wrapped up in a big brand-new dataset. We'll see if it becomes adopted as a cornerstone for figuring out this problem - the problem of basically weaponized social media. How do you fight that?

Maybe we have a first dataset on there. But there's a lot of concerns with that.

What data policies do we need? What exists?

Scott: So what do you think our people should do from a policy perspective? What exists? What should exist in the future in order to enable an ideal landscape for AI to flourish but privacy to still be a thing?

Susan: What's the balance? Man, this is so early. Like, throwing a dart about what the right balance is, is really, really, hard.

Scott: It's like 1900 trying to talk about electricity.

Susan: Exactly. I mean, I think first of all, without talking about restricting what is and isn't there. Susan's personal take is, openness is the number one thing. Being open about what data's being collected and what it's being used for. I'm not saying restrictions anything like that, but that will help. That'll help frame the conversation, and help educate consumers and individuals and companies. That way we can go into an informed future and make more informed decisions. I can guarantee you that whatever is being hidden right now, eventually will come out. That's the nature of the digital age. If you're more open right about now, it'll go a lot easier when the harder privacy laws inevitably start hitting.

Scott: If you're asking me to make a prediction, "Hey, how are people going to feel about this in the future or what's going to happen?" I think if you just look back into the past - year 2000, Internet hits the world in a big way and everybody's afraid of it. They're like, "I don't know if I'm going to go on there. Is this thing watching me? I have a webcam. Oh, no, it can see my entire life. Should I put my credit card in here? I'm not going to trust anything. How could I get anything through the mail, through eBay and trust that?"

There's a lot of things that have to be figured out. But, they get figured out. So, a similar thing with AI. A lot of things have to be figured out. Do you have to fear everything? No. Are people going to fear everything at some point in time? Yes. Are they going to be resolved? For the most part, yeah.

Susan: Fear is not a good way to approach the future, no matter the problem.It should be a motivator to understand, but not to stop you from going into the future. Because no matter what, there's only really one guarantee, the future is going to happen. So you can either be part of shaping it, or you can hide in the corner.

Scott: In the back and watch what happens.

But to answer our big question, how is data going to influence the future of machine learning? Okay, so we've got to worry about privacy, you've got the different types of machine learning. We talked a bit about text, audio, images, other stuff.

What's the future going to hold?

Susan: I think that we're going to see more and more of these big data dumps trying be the cornerstone of solving a problem.

Scott: Like a jumping off point?

Susan: Yeah, a jumping off point. Especially, honestly, from bigger companies, because now, just the fact that Twitter released it. I'm already calling it The Twitter Dataset! Their name is out there and they're looking like they're doing something about this problem. So it's good PR, although it's really challenging and it can be a disaster if you do it wrong. But, we're going to see more of those cornerstone datasets come out there, help define these problems with data.

Data defining the problems. That's a big piece of what's going to shape what the machine learning world looks like five, ten years down the road.

Scott: This is a really interesting part of AI, in that the data that is collected, labeled, used to train models, has transferred very heavily from being small academic datasets to very large datasets that are captured by companies and used to build models. So this is why you see talent moving from academia to big companies. That's not really going to end because that's where all the data is. The big companies have the big data and in order to do AI well, you need big data.

Susan: And, people that want to solve problems want to solve problems where the problems are interesting. Early on it's interesting in the public sector and later on it becomes interesting in the academic world. It gets its seeds in academia, flourishes in public, and then goes back to academia.

Scott: Yeah, I think so. Because, a lot of the baseline problems will be solved, people will be tired of it, it'll be very common place: "Yeah, yeah, yeah, the AI system, and whatever. Yeah we got our data flywheel and we're collecting what we're doing, and doing all the things." But, what's the new good stuff, general AI, or whatever, where's that going to be seeded? It may be in the companies, but probably more like there'll be some kind of data partnership with academic institutions or something like that.

Susan: You know, an interesting kind of area that data, this is pure speculation here, but where data could really start playing a different role is government-supplied datasets that you must conform to if you're going to release something.

Scott: Oh, yeah, like it has to fit these rules.

Susan: Yeah. Or, "You must have learned from this dataset, and we're going to test you against your ability to deal with these datasets."

Scott: Kind of an adversarial, like "If you can't deal with this, then you're not a good enough model?"

Susan: Well, think about judging. We'll make up a hypothetical doctor program. They have their test set of diagnostic cases that you must pass.

Scott: Answer yes or no.

Susan: Yeah, this becomes how to board-certify an algorithm.

Scott: A really good point. Machine learning models in the future will probably be tested a lot like humans are now. There's a curriculum and tests that you should pass and maybe you specialize in certain areas, but if you go work for one company the things that you learn there will probably also be transferred to other companies. Maybe it's not trade secrets or something like that, but sort of underlying ways that humans work. It's what happens for humans now. You go work for one company, fine. You leave, you go work for another company. Did you forget everything that happened for those years that you worked for that one company? No. So you bring those along with you. People will start to think of models that way.

Susan: Yeah, it's a really interesting world, just on the data side. Just so much that goes into curating a really good dataset, publicizing it and getting it accepted and all the areas.

What are the future datasets going to be?

Scott: I think it's going to be interesting. I think we are just in the very beginning stages. It's like the first railroad was built across the US or something, now there's going to be 3,000 railroads. It's a similar type of thing. The first telephones were a long time ago, but it took a very long time after that until everybody had a telephone. It's going to work it's way into every part of life and, at least from my perspective, people shouldn't be too afraid of it because it's going to make your life so much easier.

So as long as the path is taken in a way that isn't crazy, which, companies are pretty non-crazy now. They don't want to scare you off from being a customer. Then it's like, "Hey, this is going to evolve. It's going to make your life way easier. Things are going to be more efficient. Then, you'll just be very glad."

Similarly to text messaging or Facebook or something like that. Hey, you're giving up all this data and some privacy and things like that, but your life is so much better now that you can connect to your network that is spread across the world, essentially. Right?

Susan: Yeah. I mean, as much as we are definitely challenged by the privacy, where it is today, no one is talking about giving up their connectivity. Well, I should say, I definitely know people who say they're going to drop off social media, they're going to drop off and you never hear from them again.

Scott: But, are you going to stop using Google just because they used your search terms to help train their models to serve you better search terms? Probably not, right?

I think data obviously plays a big part now, but it's going to play a very big part in the future. You'll get your baselines set over the next few years, but then there'll be all these offshoots that the rest of the world and life just starts to become easier because you get that labeling, flywheel going. "Hey, here's some data. Hey, we labeled it. Hey we trained a model and then it did this task."Then people will become used to it and they go, "Well, this is awesome. I don't have to do all these menial tasks anymore."

Susan: It gives you that bootstrap. So one more final interesting aspect of all this is people don't realize it, but the first hour is the hardest hour. The ten thousandth hour is way easier than the first hour. Even if the first hour isn't as targeted as you'd like it to be, just having someone to have kicked out that first hour for you saves you so much work and effort, mentally, because now it gives you a structure- what the ten thousand hours might look like.

Scott: It's something to build off of. If you just have an example, you have a template, and it's like, "Okay, maybe I'll add one hour from my time to make that." Now it's a two hour dataset, and then it starts to build a community around it.

Susan: Yeah, these things are like little seeds. These little datasets are just seeds.

Scott: You've got to form it in the right way and then it grows.

If you have any feedback about this post, or anything else around Deepgram, we'd love to hear from you. Please let us know in our GitHub discussions .

More with these tags:

Share your feedback

Was this article useful or interesting to you?

Thank you!

We appreciate your response.