In this series, I'm focusing on the basics needed to start working in Vue 3 for people who might have some experience in Vue 2, but who haven't yet built anything in Vue 3.

Check out my previous posts in the series:

Today, I'll introduce how to use methods, watch, and computed in Vue 3, and I'll also give a general comparison of watch and the new watchEffect.

Introduction

The way I learn best is by connecting abstract concepts to a real world situation, so I tried to think of a simple, realistic situation for using methods, watch, and computed. The situation would need to demonstrate the following:

doing something to data properties to change them (using

methods)making something else occur (i.e, a side effect) because of a change to the data properties (using

watch)returning a value that is calculated based on data properties that have been changed (

computed)

I will use a real-world example of a company with employees and managers; the logic will help keep track of number of employees, number of managers, and total company headcount. Not the most exciting example, but I really just want to keep it simple.

Methods

One of the first things I need to be able to do, whether I'm using Vue 2 or Vue 3, is be able to make stuff happen with methods/functions (note: I'm using the terms functions and methods interchangeably in this section). The magic of Vue is its reactivity, so local state updates automatically as stuff happens. The stuff that happens is often triggered by methods.

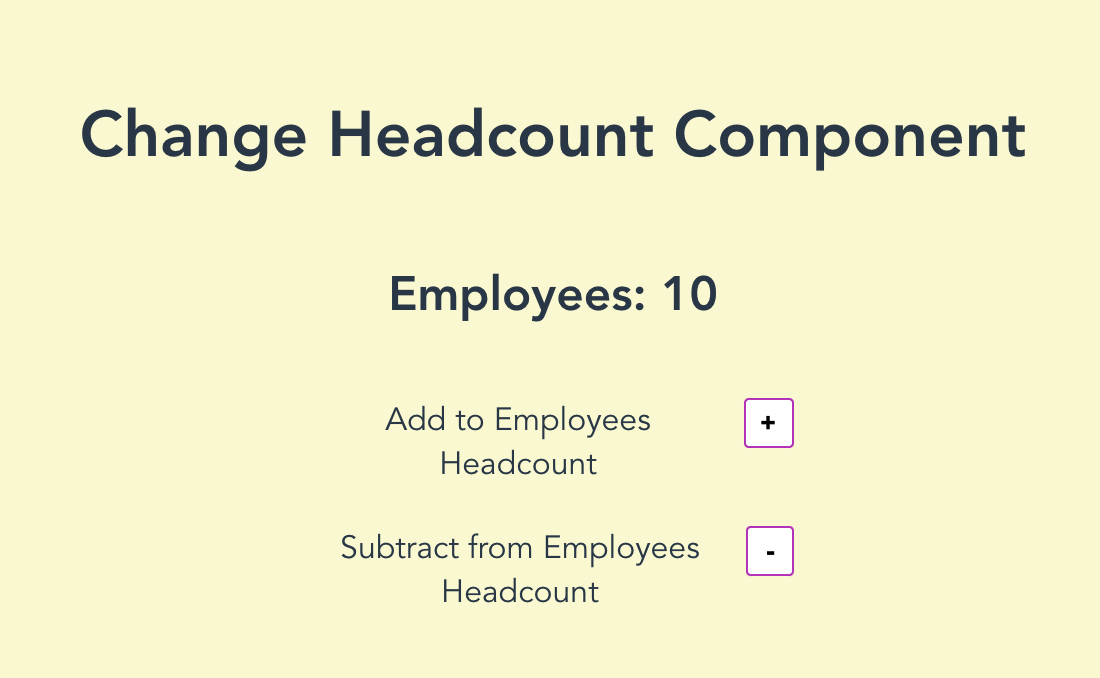

In my real-world example, I want to create a component that has a variable to represent the number of employees with buttons I click to add or subtract the number of employees, changing the headcount. I'll write functions to perform these basic actions.

Here's what the rendered component looks like:

I am familiar with the Vue 2 way of adding functions to the component: add each function to the methods object:

<script>

export default {

data() {

return {

numEmployees: 10,

};

},

methods: {

addEmployees() {

this.numEmployees++;

},

subtractEmployees() {

this.numEmployees--;

},

},

};

</script>And the following line from the template shows that Vue 2 and Vue 3 are no different in how the methods are invoked in the template:

<button @click="addToEmployees()">+</button>However, Vue 3 is different now in regards to where we write the methods in the script. In Vue 3, I can now write my functions inside the setup function, which runs very early in the component lifecycle (before the component instance is even created). I no longer have to write all my functions in the methods property of the options API.

In this example, I have written two basic functions, and those functions are not separated into a separate methods block like in Vue 2, they are inside setup with the related logic like the variable for numEmployees. I can make the functions available to the template by returning an object that includes them:

<script>

import { ref } from "vue";

export default {

setup() {

let numEmployees = ref(10);

function addEmployees() {

numEmployees.value++;

}

function subtractEmployees() {

numEmployees.value--;

}

return { numEmployees, addEmployees, subtractEmployees };

},

};

</script>Notice that there is no keyword this when referring to numEmployees. Methods that are inside the setup function no longer use the keyword this to refer to properties on the component instance since setup runs before the component instance is even created. I was very used to writing this-dot everything in Vue 2, but that is no longer the experience in Vue 3.

The use of ref() surrounding the data property is something I introduced in the last post, and it's important here. For reactivity to work in Vue, the data being tracked needs to be wrapped in an object, which is why in Vue 2, the data method in the options API returned an object with those reactive data properties.

Now, Vue 3 uses ref to wrap primitive data in an object and reactive to make a copy of non-primitive data (I've only introduced ref so far in this series). This is important to methods because it helps me understand why I see numEmployees.value inside the function rather than just numEmployees. I have to use .value to reach the property inside the object created by ref and then perform the action on that value property. (I don't have to use the .value property in the template, however. Just writing numEmployees grabs the value).

Writing all the methods inside the setup function may seem like it would get messy when there is more complexity going on in the component, but in practice, related logic could all be grouped together to run within its own function. This is where Vue 3 starts to show its strengths. I could group all the logic for updating headcount into a function called updateHeadcount, then create a separate JS file where that logic lives. I'll actually name it useUpdateHeadcount.js, which is Vue 3 best-practice for naming this type of file (the convention of starting composables with use is discussed in the Composition API RFC in this section). Here's the useUpdateHeadcount.js file:

import { ref } from 'vue'

export default function useUpdateHeadcount() {

let numEmployees = ref(10)

function addToEmployees() {

numEmployees.value++

}

function subtractFromEmployees() {

numEmployees.value--

}

return { numEmployees, addToEmployees, subtractFromEmployees }

}Now, in my component, I just have to write this in the setup function:

<script>

import useUpdateHeadcount from "../composables/useUpdateHeadcount";

export default {

setup() {

const { numEmployees, addToEmployees, subtractFromEmployees } =

useUpdateHeadcount();

return { numEmployees, addToEmployees, subtractFromEmployees };

},

};

</script>

Composables

Notice that I imported the useUpdateHeadcount file from a folder called composables. That's because these functions to separate out logic by shared concerns are known as composables in the Vue 3 world. I'm not going to go over all the details of how I wrote the composable and brought it back into the component file because I'll be doing a later blog post in the series about composables. In fact, I don't even have to use a composable; I can just write all my logic in the setup function since it's a very simple component. But I wanted to also make it clear that as the component gets more complicated, there is a strategy for organizing the logic, and it's one of Vue 3's most exciting features.

Watch

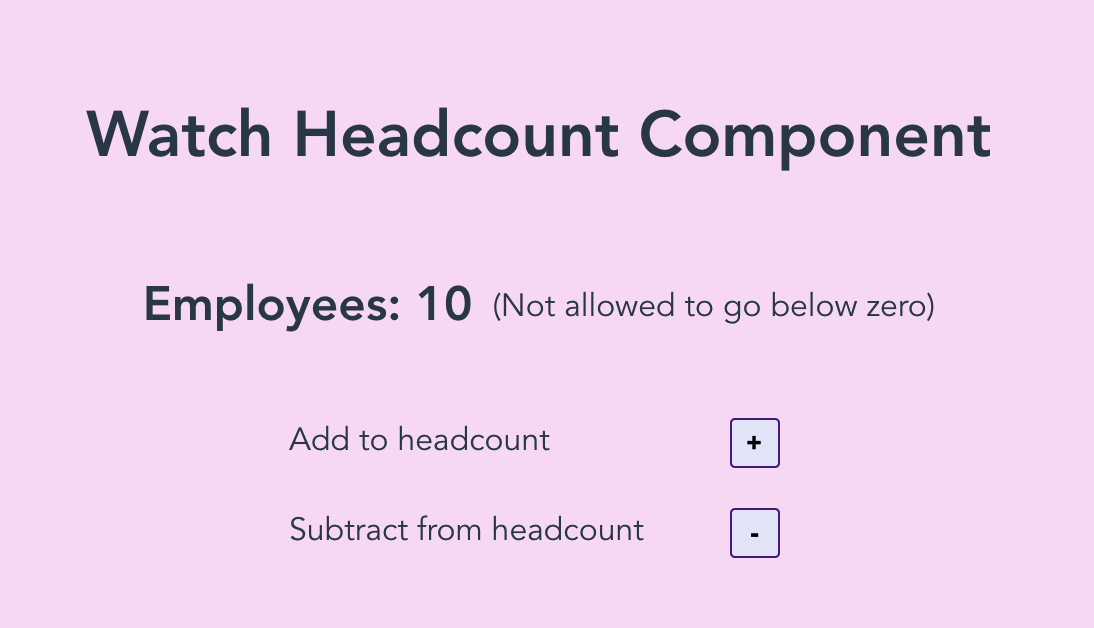

watch is basically the same in Vue 3, so I am happy to know that I can use it as I have before. In my example, I want to track the value of numEmployees to make sure it doesn't go below zero, since it's not possible to have negative human beings as employees.

Here's my rendered component. It looks the same, but I added a disclaimer that the headcount cannot go below zero.

This restriction - not going below zero - will be managed by the logic in watch:

watch(numEmployees, () => {

if (numEmployees.value < 0) {

numEmployees.value = 0

}

})I specify which data property to track (numEmployees) as the first argument, and a callback as the second argument. Inside the callback, I have my logic that causes the side effect. If numEmployees reaches below zero, that side effect happens, setting the value to zero. The callback makes sure the side effect happens on the next tick following the value reaching below zero.

watch will not be triggered until that specific reactive property is changed, so if I want it to run immediately when the component is created, I can add an object with immediate: true like this:

watch(

employees,

(newVal, oldVal) => {

if (employees.value < 0) {

employees.value = 0

}

},

{ immediate: true }

)The callback argument can also take two arguments for the new value and the old value, which makes watch useful for doing logic based on the previous state of the reactive property or just checking if a property has been changed (i.e. it's a great debugging tool):

watch(employees, (newVal, oldVal) => {

console.log(oldVal, newVal)

})As for comparing watch in Vue 2 versus Vue 3, the only difference is that in Vue 3 I can now place watch inside the setup function. Like methods, it no longer has to be separated out into its own section as an option property on the component instance.

However, Vue 3 also has added a similar feature that gives some different capabilities from watch: it's called watchEffect.

watchEffect

Vue 3 keeps watch the same, but it adds watchEffect as another way to cause side effects based on what happens to the reactive properties. Both watch and watchEffect are useful in different situations; one isn't better than the other.

In this example, I will add another reactive property to the component - managers (numManagers). I want to track both managers and employees, and I want to restrict their values going below zero. Here is the component now:

The reason I added a second reactive property is because watchEffect makes it easier to track multiple reactive properties. I no longer have to specify each property I want to track as the first argument of watch. Notice that I don't have a first argument to name the properties I'm tracking:

watchEffect(() => {

if (numEmployees.value < 0) {

numEmployees.value = 0

}

if (numManagers.value < 0) {

numManagers.value = 0

}

})Unlike watch, watchEffect is not lazy loaded, so it will trigger automatically when the component is created. No need to add the object with immediate: true.

watchEffect is useful when I want to track changes to whatever property I want, and when I want the tracking to happen immediately.

watch is useful when I want to be more specific about tracking just one property, or if I want to have access to the new value and/or old value to use them in my logic.

It's great having both features!

Computed

One of the nice things about the Vue template is that I can write logic within double curly-braces, and that logic will be calculated based on whatever the values are represented by each variable:

<h2>Headcount: {{ numEmployees + numManagers }}</h2>This will show a number which has been calculated, or computed, based on what numEmployees and numManagers are at the current point of time. And it will change if either of those data for numEmployees or numManagers change.

Sometimes, the logic can get complicated or long. That's when I write a computed property in the script section, and refer to it in the template. Here is how I would do that in Vue 2:

<script>

export default {

computed: {

headcount() {

return this.employees.value + this.managers.value;

},

},

}

</script>The computed property is another option that is part of the options API, and in Vue 2, it sits at the same level as methods, data, watch, and lifecycle methods like mounted.

In Vue 3, computed can now be used in the setup function (I bet you didn't see that one coming). I have to import computed from Vue like this:

import { computed } from 'vue'To compute the number of employees and the number of managers, giving me the total headcount, I could write a computed like this:

const headcount = computed(() => {

return numEmployees.value + numManagers.value

})The only difference is that now I pass into the computed method an anonymous function, and I set it to the constant for headcount. I also have to return headcount from the setup function, along with everything else I want to be able to access from the template.

return {

numEmployees,

numManagers,

addToEmployees,

subtractFromEmployees,

addToManagers,

subtractFromManagers,

headcount, //<----

}Putting It All Together

At this point, I have logic that does the following:

Adds or subtracts to the number of employees (numEmployees) or to the number of managers (numManagers)

Makes sure employees and managers do not go below zero

Computes the total headcount based on any changes

Conclusion

And that wraps up this post in the series. Stay tuned for upcoming posts that cover topics like ref and reactive, composables, and the new v-model. And as always, feel free to reach out on Twitter!

If you have any feedback about this post, or anything else around Deepgram, we'd love to hear from you. Please let us know in our GitHub discussions .

More with these tags:

Share your feedback

Was this article useful or interesting to you?

Thank you!

We appreciate your response.