The Trouble with Word Error Rate (WER)

January 3, 2019 in AI & Engineering

In the spring of 2017, Google announced that their voice recognition WER (word error rate) had fallen to just 4.7%-putting it on the par with human transcriptionists. "Wow!" said the world. Highly accurate speech recognition is changing how we interact with computers, how we advertise and so much more. Too bad that a 4.7% WER is advertising bunk. Several large companies have announced similarly low rates-and these low rates are real, but here's the catch: They managed to get human-level accuracy by training their ASR (automatic speech recognition) systems on a small language corpus, like the National Switchboard Corpus.

The National Switchboard Corpus is a well used (overly-used) database of phone calls that have been carefully transcribed for linguistics research. When companies announce that their new speech recognition system has impossibly low word error rates, it's because they are trained and validated on this very limited data set. No company has yet to reliably deliver 4.7% accuracy on everyday audio-the sort of audio that comes through call centers and cloud conferencing companies and needs to be transcribed.

In fact, even the most highly trained (and expensive) human transcriptionists would struggle to get 4.7% accuracy on regular "wild" audio data. When data scientists look at different speech recognition APIs (ASR products), they evaluate them according to several metrics, WER being a principal one. Yet, WER is not a perfect metric. This is because WER is strongly affected by:

Different kinds of noise

Crosstalk

Accents

Rare words

How transcripts are (or aren't normalized)

1. Noisy Voice Data Lowers WER

Have you ever wondered why the NATO phonetic alphabet exists? The NATO phonetic alphabet (NATO-PA for short) is the cool words that pilots use to communicate (both in real life and in the movies). You've heard it:

"Delta bravo eight nine six cleared to land two six right."

The NATO phonetic alphabet was created to address the very same problem that causes WER to vary greatly for any one system: the variety of accents in language and the noisiness of communication methods make comprehension difficult. In 2018, top-performing call center representatives all know the NATO-PA because the phone-POTS and VoIP-are noisy, compressed communication media.

Today, we have a variety of voice communication channels, but we still face the same problem that WW2 pilots faced: The phone systems our customers call us on introduce a lot of noise into the voice data. The noise may come from problems in the line, compression, and ambient noise.

Line Noise

People call businesses from office phone lines, from their cell phones, even occasionally from a sat-phone. All these systems introduce noise from bad or weak connections: bad jack, bad signal, squirrely satellite. All the long-distance communication systems introduce noise somehow and can seriously hamper ASR systems. But, line noise is not the only form of noise that causes problems for transcription.

Compression

All voice communication systems, VoIP, chat, Whatsapp and so on compress their audio. Compression means that the phone systems are designed to be more efficient by removing a lot of information. That makes talking cheap, but it also means that you can't understand as much. Have you ever tried understanding a new word over the phone? Impossible, no?

Ambient Noise

Few of us have a landline anymore. Plus, all of us are very busy. This means that when we do call the companies we buy from, we are likely calling from noisy environments.

Noisy office

Echo-y conference room

Crowded restaurant

Rambunctious playground

Siren-filled street

Windy beach

To make matters worse, there is no way to control for the quality of the microphone or how far away people speak from the conference room microphone. The fact is, most real-world data is going to be noisy. Therefore, when using a speech recognition system to decode your voice data, make sure it's trained on your kind of noisy voice data.

2. Crosstalk: Humans Come in Pairs

There is another form of 'noise' that really dizzies brains and off-the-shelf speech recognition systems: crosstalk. As long as we are in the room, know the topic and the speakers intimately, it isn't hard to follow a conversation when two people talk over each other. You may not even realize when someone starts their sentence before you can end your's. However, recordings of human conversation are hard to follow and even harder to transcribe. Most of the difficulty arises from crosstalk-the moment when two people speak at the same time. Crosstalk is incredibly common-it is a natural and somewhat unavoidable part of human conversation. Due to the fact that humans and machines have trouble sorting out the words said in crosstalk, you get unpredictable results when it gets transcribed.

How do you represent simultaneous speech in text?

What if crosstalk makes things inaudible for humans and machines?

Is it more important to transcribe one speaker versus another?

There are few standards developed to deal with the "crosstalk error." As a result, what gets transcribed is done in many different ways: sometimes correctly but in the wrong line (so it looks like deletion AND substitution errors at the same time) or completely omitting one speaker's words entirely. Naturally, such confusing standards would confound ASR and greatly impact WER. Data scientists should therefore consider how much crosstalk there is likely to be in their data. Web conference audio data likely has a lot and YouTube recipe videos likely have little, unless it's Giada attempting to teach Nicole Kidman and Ellen Degeneres to cook.

When choosing a speech recognition API, look at where the errors occur. If the crosstalk errors are not important, consider re-calculating the error rate for yourself.

Newsletter

Get Deepgram news and product updates

3. Accents: They're Sexy and Confusing

English is spoken natively by nearly a billion people. You can imagine that in such a large number of speakers there is going to be some variety in accents. Plenty of academic research (and our own experience) tells us that people often have trouble recognizing accents they are unfamiliar with-even when these are dialectical accents (from their own language). As you can expect, speech recognition systems also need to be trained on different accents. The NATO phonetic alphabet we mentioned above was created to address two problems with aviation communications: noise and accent. At the beginning of World War II, the Australian, American and British pilots had trouble understanding each other over the radio. Several radio alphabets were devised as a fail-proof system to communicate vital flight data across English accents. These were eventually formalized and standardized in the 1950s for use in commercial aviation. If we could train all English speakers to spell out every word they say with the NATO-PA, speech recognition would be a solved problem. Such a proposition is absurd.

When companies like Google announce a 4.7% WER, they are effectively saying our speech recognition systems are really good at understanding this one accent, in this kind of a noise, using a known and limited list of words. That's not real life.

In a global economy, where our suppliers, employees and customers come from every corner of the globe, no one speech model can yet accurately transcribe every conversation. Even Silicon Valley giant Google isn't proficient enough to account for all English accents. Yet, in globally competitive economy, leveraging diverse voice data at scale is soon to be indispensable. Just like humans need to become familiar with an accent or a speaking style they are unfamiliar with, speech recognition models need to be trained to do the same.

4. The Words that Matter are Rare

We're all using the words everyone else is using. This is an observation made by greats such as Aristotle and George Carlin. And it has deep meaning for evaluating a speech recognition API. Most of the words we use are the "glue" of language.

Yes

The

And

Going

I

They

So

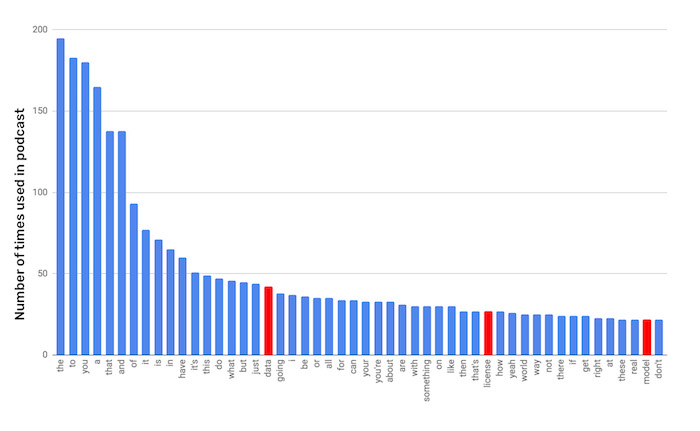

From a linguistics point of view, these glue words collectively carry a lot of meaning. You change their order, add an adverb or adjective and you've said a lot. However, this also means that the rare words, the 80% or so of words we use only once or twice in a conversation, are individually loaded with meaning.  Take a look at an episode of our podcast and you'll see we used 922 unique words. Here we see the 50 most used words. This means 5% of the individual words account for 50% of all words said! Notice that 3 of the words are "meaningful" and the rest are just grammar. These are the meaningful words that actually made it into the top fifty most used words. Despite this they only account for 1.7% of all words. Most truly meaningful words are used less than 2 times in the 30 minute podcast (less than .03%).

Take a look at an episode of our podcast and you'll see we used 922 unique words. Here we see the 50 most used words. This means 5% of the individual words account for 50% of all words said! Notice that 3 of the words are "meaningful" and the rest are just grammar. These are the meaningful words that actually made it into the top fifty most used words. Despite this they only account for 1.7% of all words. Most truly meaningful words are used less than 2 times in the 30 minute podcast (less than .03%).

These rare words are the ones that ASR systems often fail to recognize. In our businesses and sciences, we have extra words: our own common glue words and our own rare used-once-in-a-conversation words. These words are called jargon. Jargon words are the loaded-with-meaning words that general model speech recognition APIs often miss.

"Fraudulent payment"

"Action item"

"Convolutional neural network"

"SaaS"

"Exec-dev estimates"

They are also usually the words that companies most want to transcribe accurately. Even a low WER transcript may not be useable if the keywords-the jargon-are not well transcribed. Since they are rare, missing them does not strongly influence the WER, yet since they are important to us, transcribing these incorrectly can be extremely debilitating. In other words, since the information-dense words are rare, a transcript may boast a great WER, but still not be useful. Always make sure you know what words matter to you in a transcription. When your data team evaluates automatic speech recognition transcripts, they should make sure that their keywords are accurately transcribed across all their audio data.

5. Normalization Discrepancies

On its face, the word error metric seems straight forward: how many words are transcribed incorrectly when compared to some 'correct' version. However, to calculate WER you must decide what counts as a word and what counts as an error.

Does punctuation matter?

How about the standard um, uhs, and uh huh's of normal human speech?

Should numbers be written in Arabic numerals: "53" or written out: "fifty three"?

Are normal contracted words like "it's" written as two words "it is" or as the contraction?

Are minor discrepancies such as pluralizations wrong?

What about phonetic reductions like "gonna" or "runnin'"?

The variation in word-distance introduced by not normalizing results in WER causes great unpredictability in transcript outputs. When you compare speech API outputs to your "perfect" transcript, you have to normalize the transcripts so that you are comparing apples to apples, and not apples to pickles or tangerines.

Know your WER

When looking at word error rates remember to consider:

1. The Kind of Audio Recording Being Transcribed

Is it phone calls?

Is it crisp, bassy podcast audio?

Is it cloud conference data?

2. The Kind of Speaking Happening

Is it a fast conversation with lots of crosstalk?

Is it a monologue (radio, TV)?

3. Who is Speaking

Do the speakers have the same accent?

Do the speakers have an accent not supported by a particular ASR?

4. The Subject Matter of the Conversation

Can the ASR recognize the words and terms that matter to you?

5. Normalizing the Data

What are you comparing your transcript to?

What punctuation and structure should your transcript have?

Have you converted dollar amounts and phone numbers to a consistent format?

To get a better read on how well an ASR system is performing on your audio data, also check out How to Evaluate a Deep Learning ASR Platform.

If you have any feedback about this post, or anything else around Deepgram, we'd love to hear from you. Please let us know in our GitHub discussions .

More with these tags:

Share your feedback

Was this article useful or interesting to you?

Thank you!

We appreciate your response.