What Are the Top Mistakes in Deep Learning? — AI Show

December 7, 2018 in AI & Engineering

Share

In this blog post

- Don't try to do something that is impossible.

- Trying deep learning first.

- Don't throw away your standard stats and machine learning techniques.

- Validation versus training

- Overfit your hyper parameters.

- Choosing the wrong learning rate

- Not normalizing your input data

- More examples of common pitfalls

- The process side of the house is to me the biggest problem here.

Scott: Welcome to the AI Show. Today we're asking the question: What are the top mistakes in deep learning?

Susan: We've got huge ones! We make them all the time.

Scott: The mistake is the rule in deep learning. You make nine mistakes and one maybe good move.

Susan: How are you gonna find new things if you don't make mistakes?

Scott: It's frontier tech, right?

Susan: There's just so many fun pitfalls you can fall into that everybody's fallen into.

Scott: What do you think the big areas are?

Susan: I think that there's really two major areas. There's just analyzing the problem; the basics of analyzing whatever problem you're going down and the pitfalls around there. Then there's the model and data. If you don't analyze your problem correctly then it really doesn't matter what you do with the model and data. You've fallen off the tracks. Once you finally got a good understanding you can get down there and fall into brand new pitfalls. Have you fallen into any analysis problems there, Scott?

Scott: I'd say there's too many to talk about, but yes. Analyze the problem, make sure your data is good, these are all good traps. Make sure your model is actually a model that we'd actually be able to perform the task you care about and then in the end you actually have to train it too. Training has its own history, as well. Probably I can name some things that I've done that are not good. Some of it just when you're doing deep learning you're doing programming. Programming is hard. Copy pasting, you're reusing old code, you're iterating as you go along and you're using the problems and errors that you're getting to help you along until you finally get water through the pipes.

Susan: That's really important: water through the pipes.

Scott: But usually once you first get water through the pipes and you get your first result everything is totally wrong anyway, so you're backtracking. Okay, where did that mistake come in?

Susan: Comes out more mud than water.

Scott: How do you get the pieces to fit together in the model at all? How do you get even a few pieces of data into the right form to be jammed into the model? Then the model finally has to output something and its output doesn't make any sense at all. But biggest thing is trying to learn an impossible task.

Susan: I've done that.

Don't try to do something that is impossible.

Susan: I've a fairly good rule of thumb for that one. If you as a human looking at your training data can't learn the task, then I can pretty well guarantee you that no matter how good of a model builder you are it's probably not gonna be able to learn that task.

Scott: Even if you think you can learn it, but if you ask somebody else and they're like, no that's a totally different thing. This is something like summarizing a scientific article and its jammed full of information. People would summarize it in different ways. Maybe that's not an impossible task, but that's a very, very, very hard task.

Susan: The big point here is: pick battles that are winnable. Make sure you're doing the steps necessary to figure out that this is a winnable battle. Don't let yourself believe that magic black box that is deep learning will be able to learn anything so long as you throw in enough data at it.

Scott: There's so many ways that it can go wrong. You don't want the number one reason of just this isn't even possible to take you down. Pick something that maybe a human could do. This is a good rule of thumb. If a human could do it with maybe a second worth of thinking and come out with a reliable answer every time, maybe that's something a machine could do.

Susan: The second half of that is truly important. A reliable answer. What does that mean? An objective answer. Something that if you had ten humans and you asked them the same question, you would get probably nine of them at least agreeing. Because if you have five of them saying one thing and five of them saying another thing, even if they're super positive that's the right answer, a machine's gonna have a very hard time figuring out what side of those five to be on.

Scott: Yeah ask ten people what five times five is. Okay, maybe you can teach a machine how to do that. We know that for sure. But ask them what the meaning of life is or who won the argument.

Susan: Was that dress blue or was that dress ... Well maybe that one a machine could figure out perfectly.

Trying deep learning first.

Susan: Deep learning thinks it's everything.

Scott: Pump the brakes here a little bit.

Susan: What is the simple approach? Also, you'd be surprised, just the most basic of algorithms can solve some really, really hard problems, or what we think of as hard problems. Just add it all up and find the mean and suddenly you got 90% of your answer in a lot of cases. Don't skip to the most complex possible huge-chain answer that you can right off the bat.

Scott: You have to load up a ton of context and tools and the know-how in your brain and time and the iteration cycle on deep learning is so long that it's hard. You could be doing something with just regular stats or traditional tree based machine learning technique or something that would go through the data and you'd have a result in five minutes. That often is better than waiting two days for deep learning. You want to get on that track, like the five minutes.

Susan: Even then, just doing a simple least squares fit. I've done that so many times and that is an amazingly great, quick way. Say, hey, this is a tackle-able problem. Also, sometimes the answer is right where you need it to be.

Don't throw away your standard stats and machine learning techniques.

Scott: Go to those first. If you think this isn't performing as well as it should and:

I've turned lots of knobs,

I have a ton of data,

I have the computing power,

I have the time to go through and try to figure this out Maybe try deep learning then. And it's not impossible. What about data?

Susan: I'm gonna tell an embarrassing story. I'm going to hope most people have had the same embarrassing story. I started playing around with deep learning probably just for fun. Not deep learning, just machine learning in general, about 10 years ago, 15 years ago. I was playing around with little things and then I hit the stock market like everybody does.

Scott: Yeah, first thing. Oh, machine learning, here we come!

Susan: I'm gonna predict the stock market! I started building my little model and man, it was accurate.

Scott: Super accurate?

Susan: It was crazy accurate. I was like, I'm gonna be a millionaire! What did I not do properly?

Validation versus training.

Validation versus training

Scott: What you're trying to do is set up the problem, so I'm gonna give you this data and you have to learn from it, but then I'm gonna hold this other data out, which is true data, again, but the model's never seen it, and now I'm gonna show it to you and see how correct you are. Well, if you don't do that properly, then you really fool yourself.

Susan: You can delude yourself so amazingly well. And the great thing about this particular trap is that there's so many variations to this trap. Let's go to the audiobook world and you're trying to do something like speech recognition. You have 500 audiobooks and 18 people reading those audiobooks. You could split your data one of two ways: off of audiobook or off of people.

Scott: Well there's 500 audiobooks, so ...

Susan: I can guarantee you if you do it off of audiobook you won't be able to use it in the real world. There's 500 audiobooks, but now you suddenly look a lot better than you actually are because you got the same person in your train versus validates.

Scott: It learned how that person spoke in the other books and even though it hadn't heard that exact audio, it's heard that voice before and it's learned a lot form that voice and so it can do a good job on it.

Susan: It's not just, hey: "I'm gonna randomly select." I have unfortunately learned this lesson on several times in my life. You want to know how the model performs in the wild. Real, wild data. This is a hard thing to just keep track of, especially in deep learning because it takes so long to do your experiments. It's easy to say what if I use this? What if I do this? What if I look over here? If you train just once on one of your validation data sets, you have a big problem. You can't undo that. If you've been training your model for the last three months and you then spend a day training on your validation data set, you might as well throw that validation data set away, put it in your training data set, or start over on the model.

Susan: Hopefully you had a checkpoint before you did that.

Scott: Or go back. Go back into a checkpoint.

Susan: You contaminate that model and you are done. And it can happen so many ways you don't even realize it. You get a new data set you didn't realize was actually derived data set and it has different IDs associated with the thing it was derived from and suddenly, wow, I'm doing really well on this, except for it's not real.

Scott: Training a model is not a reversible process. There's no undo button.

Susan: It's very incredibly easy to mess up your various sets of data, so treat them wisely. But, you know what's another great way to mess up training versus validate?

Scott: What?

Overfit your hyper parameters.

Scott: Oh yeah, for sure. You're always picking how wide should it be, how deep should it be, how many input this do I need, how many that? What should my learning rate be? And all these different hyper parameters and then you try to use it on some wild data and things aren't working. Why aren't they working?

Susan: What happened? I ran 10,000 tests, each one tweaking it to be the best possible result on my validation. Why isn't that matching reality?

Scott: You're training yourself a little bit here. It isn't that the model got adjusted so much, it's that you are thinking: "Oh, what if I tune these knobs a little bit?" Now it does really well on your validation data set, but if you give it some real wild data, it doesn't do so well.

Susan: It's hard to grasp at, but the first time you really truly run into it and smacks you in the face, you definitely feel it hard. It's like that big gap between validation and reality is huge. There's still even more ways you can mess up your validation set. We could talk about this forever.

Scott: There's a good way to combat this, which is you have your large training data set, then you have a validation data set, then you have another validation data set, then another validation data set, then you at least have these backups. Hey, you can test over here, test over here, test over here, get your hyper parameters where you think you need them, and then test them on these other data sets that are maybe they're small too like your validation data set, but at least it's giving you a little cross check.

Susan: Do what you can. Also, on that note, grooming these sets as time goes on is important. Just like you're talking about setting aside a secret or whatever you wanna call these additional data sets.

Scott: Test validation secret.

Susan: There's a lot of different ways to split these up, but if you're getting data over time, make sure that you keep on adding to these sets over time, because data changes over time. The English language changes over time. All it takes is one popular new song and people shift their language a little bit. We keep going back to the language world because that's what we think about a lot, but this is also images. Just think about how cameras have changed, just the quality settings and all that. Your average distribution of colors are probably changing a little bit.

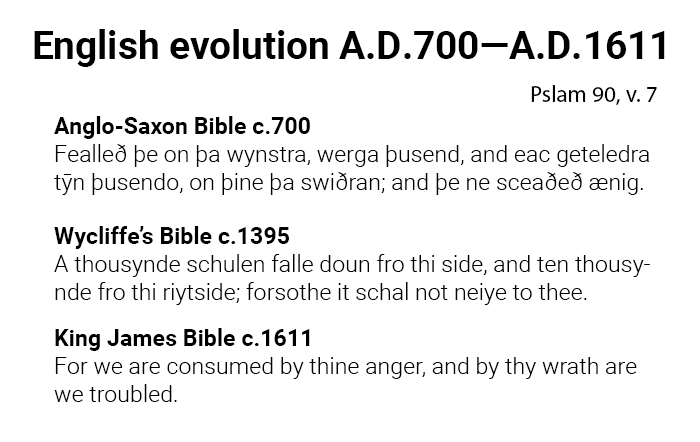

Here we see how one verse of the Old Testament changed over time. By comparing the Old English (Anglo Saxon) and Middle English (Wycliffe's) versions you can see quite a bit of sound change as well as grammatical change. The King James version is radically different, showing the changes in culture that led to serious change in interpretation. The older two versions reflect a closer translation from the Latin bible.

Scott: If you take a picture on an iPhone now versus eight years ago it's gonna look vastly different.

Susan: Or the self driving world. If you did nothing but from the 80s, a whole bunch of video from the 80s, cars would've changed a lot, clothes would've changed a lot. Do you think that would all affect how well you can recognize everything out there? All this is talking about how you manage your data and the disconnect between the reality of the data you're training on and the current real world production environment you're gonna be on. That's the big mistake that a lot of people run into. You've been in this little locked in world and then suddenly reality is somehow different. That's because you're training and your validate probably aren't as good as representing the real world as you thought.

Scott: Some other good ones are you have to choose your hyper parameters, which is how big is your network, how deep is it, how wide is it? What learning rate are you going to use, et cetera? On the topic of learning rate, if you chose too high of a learning rate, your gradients get huge.

Choosing the wrong learning rate

Susan: Blow your weights.

Scott: It tries to learn too much too fast and it learns nothing.

Susan: There's so much that goes into hand tweaking all of that stuff. One of the first things that you need to do is do a quick exploration. Whatever mechanism that you do for that grid searcher or whatever, try to find those big hyperparameter sweet spots, but then at the same time, you've gotta fight that problem of overfitting your hyper parameters. It's a real challenge and it becomes a real pitfall that you do things like wrong learning rates and then you restart and this and that and the other, then suddenly at the end of it you have a set of hyper parameters that seem to fit and you've gotten into that overfit world. Minimize how often you change it.

Scott: Try to get into a good region and then don't change it too much and then rely on your data to do the talking of shaping where the model should go. You could have too low of a learning rate too, where it just takes way too long. We've talked about this before, where you're patience limited in deep learning because things take a while, there's a lot of parameters, it uses a lot of computational power, and if you're training models for days and it's just only getting better very slowly, maybe your learning rate needs to be jacked up again.

Scott: Again, that's part of that search.

Susan: That gets into one that I've re-learned recently, which is people pay a lot of attention to data, rightfully so. A lot of attention to model structure, rightfully so, but less attention to the optimizer that they use.

Scott: I completely agree.

Susan: There's just an epic difference out there based off that. It's hard to even begin with how important that selection is you forget about.

Scott: Heuristically, it's like, if I know what my error is and I know the errors I've been making in the past, how far should I project where I should go? You can think about this as a human too. If you're walking around in the day and you keep hearing the same wrong thing, over and over, and you're like, maybe I really need to go look into that and adjust it or something. It's weighting all of that. How much of the past should I keep for now and use in the future? How much should I throw away? There's a momentum side to that too.

Susan: One way to think of it is this; going back to the classic forest problem. Dense forest and how do I get to low ground? The optimizer's are like how fast you should be walking at any one given time?

Scott: If it was all curvy right there, maybe you should do something else. But there are different programs there, basically, or different rules you should follow and that's what picking your optimizer is.

Susan: And how it adjusts that rate of walking as you go along. Those are big, huge, massive things there. What about the bottom end of a model? What kind of output errors have you run into here, Scott?

Scott: A lot.

Susan: I can give you my favorite one. If you got one right off the top, go for it.

Scott: Not outputting good results is the biggest. Outputting all zeros when you're loss function is all screwed up or whatever.

Susan: My personal favorite is outputting something that's useful in a training set, but not useful in the real world. Forgetting the difference between training and production. When you look at code and when you look at training models and stuff like that, you're going to take this thing, you're gonna wrap it in a loss function, you're going to do all these different things. I remember building my first models, when I actually tried to apply them to a real world problem, I realized that was completely not useful. The training set that I had been training against and the outputs I had been using there were giving me these great numbers of loss.

Scott: 99% accuracy.

Susan: And accuracy and I was like, oh, and I was tweaking the various setting and all that stuff. Then I disconnected the model from all that apparatus and tried to do something with it.

Scott: Yeah, feed it something real.

Susan: Suddenly I had no idea what it was actually doing. It just had this black box of data in, black box of data out, these metrics around it. You've always, always gotta keep in your mind that the whole point is not the training set, the whole point is not the accuracy number, the whole point is not all this apparatus over there, it's when you finally get to production. What is that output supposed to look like and how is it useful?

Susan: If you can't take whatever output it's got coming out there and make it useful, then you've gotta address that right away. It's like the water through the pipes that we were talking about there, 'cause water through the pipes on the training side and also water through the pipes on the production side.

Scott: Does it get sensible outputs in production-land as well?

Susan: Are you really able to take that 10,000 classes and do something with it or should have you stripped it down to those five because that's all you cared about in production?

Scott: I think some real nuts and bolts ones could help too. Like normalizing your input data.

Susan: Oh, yeah.

Not normalizing your input data

Scott: What is normalizing your input data mean? It's if you have an image, for example, and each pixel value goes from zero to 10,000, what scale should you keep it at? Should it be zero to 10,000 or should it be some other number? Typically machine learning algorithms are tuned to work well when you're talking about negative one to one or zero to one, or something like that. You should normalize your data so that zero to 10,000 now is like zero to one, or something like that.

Susan: It's staggering what normalization can do for you. You just think about humans. Think about looking around your environment. The first physical step of light going into your body goes through a normalization layer and that is what's your eye doing right now when it's stares into a light versus stares into a dark room?

Scott: It's getting smaller and bigger.

Susan: It shows you how important that step is that you physically do that. You do that with hearing too. It's a loud environment, what do we do? We put earmuffs on. We're trying to get all the sound normalized.

Scott: Or it's loud but it doesn't seem that loud. Hearing is logarithmic. There's tons of energy being pumped into your ear but it's only a little bit louder. One more on hearing. You've got two ears and the ability to swivel your head, when you listen to something, when you really wanna listen to something, you actually swivel your head and that helps your hearing. That physical motion of adjusting the two microphones in your body to be better aligned with the source makes a big different to understanding. Don't forget that lesson when you're in the machine learning world. Normalize your data, don't forget those initial purely simple algorithmic filters you could apply to data beforehand.

Scott: We haven't discussed all that much, but essentially if you're Amazon Alexa or Google Home, or something like that, they usually have seven or eight microphones on them. But humans do pretty good with just two.

Susan: Sure, however humans have the ability to turn their heads.

Scott: Yeah we can move around. You have these infinite amount of microphones.

Susan: Yeah. We've got a lot of great things there.

More examples of common pitfalls

Scott: You have a deep learning model and in there are tons of parameters. Those parameters are initialized initially to what? What do I mean by initialize? I mean you fill up a bunch of matrices with numbers, what do you fill them with? Zeros? Is that a good answer?

Susan: Bad answer.

Pitfalls were one method of hunting animals and defeating enemies in war. Now it's just a metaphor.

Scott: Very bad answer.

Susan: Very bad answer. As soon as you get to two layers everything goes out the window.

Scott: Do you fill them with all the same number? One?

Susan: Nope, it can't be the same number. Even just pure randomness is not good. We're not gonna get into the math and why, but look up some algorithms for how to fill up your parameters.

Scott: You want it round and peaked with some variance.

Susan: Based off of size, based off of number parameters.

Scott: But random still, but off a distribution.

Susan: Randomness is such an amazingly strong tool in the world. It's just crazy and that one example shows that you don't randomize things that literally will not learn.

Scott: You can stitch together networks or loss functions or pieces of code that other people have written and you use part of it, but you use it incorrectly. In other words, it should have a soft max that it's run through before it gets put in there, or it shouldn't. Do you strip those pieces off or not? This is an impedance mismatch.

Susan: To me this happens mostly going back to the training environment versus the production environment. You see this happen a lot. This is a basic one, luckily you fix it pretty quick just by changing that little piece of code. In training you may or may not need something at the end of your model that you'll strip off for production. Keeping that in mind will help save some debugging steps. Ask yourself: Is this really what I'm gonna use for production or was this here just for training? Forgetting that you've got dropout set wrong, or something like that.

Scott: You want it turned off for the evaluation inference probably.

Susan: You need to make sure your model's set for the right environment.

Scott: Drop out shuts off part of the deep learning brain basically. It's like oh, don't you think you might want that in there?

Susan: To get it in there if you've got a bunch of parameters. You can then randomly select a few of them to just ignore basically. The important thing about this is it tries to get the same level of output signal, so when you go to the production environment, you want those neurons to be there. You want those parameters to be useful, but if they were all turned on, suddenly your signal goes up, say, by 25% if you've got 25% drop out on there. You treat the evaluation side different than the train side. Some pretty important things to remember otherwise it's just not as good as it could be.

If you train your model based on speaker (narrator) then you have a narrator detector. You probably don't want that.

Scott: One of my favorite things to do though is overfitting. Which is normally a bad thing, but when you're in the water through the pipes stage, where hey, I've finally got my data going, I finally got my model built, I finally got some kind of output and I can verify that it's coming now. Now, take a really small training data set, maybe just one example or maybe 100, or maybe eight or whatever and train the model and make sure that you can very quickly get 100% accurate.

Susan: You wanna see that curve of learning.

Scott: Your error just drops like a rock because the model now has so many parameters it's able to just focus on getting those correct. All that it's doing at that point is memorizing, but if it can't memorize those eight things, it's probably not gonna do anything else.

Susan: That helps you prove that your loss function is working. It helps you prove you have some inputs and outputs there, at least in the right realm. It doesn't prove that you will have a good model structure.

Scott: No, you could have an awful model structure, but at least it has some hope.

Susan: That's your water through the pipes basic all the plumbing is involved here is working here. There's a ton of common, big, huge pitfalls. What's is the biggest one overall?

Scott: For me, I think the biggest one is like deep learning and hey, you can do anything. And it's like, okay cool, not anything, but there are a lot of things that you can do that you couldn't do before. Or it can do it better or something like that.

They think, "I'm gonna go to TensorFlow and then I'm gonna solve my problem." If that's your thought process, you gotta back up a little bit and think we need to take baby steps here because you're not going to just go download a model or an example or train it with a couple days of toying around and get a real production thing done. It's just not gonna happen.

Even from the engineering standpoint, you're not gonna do that. From the model building standpoint, you're not gonna get there basically unless it's something super simple you could've done with normal stats or machine learning.

The process side of the house is to me the biggest problem here.

Susan: Did you analyze the problem correctly from the start? This is any engineering problem on the planet.

Scott: This takes budgeting the appropriate amount of time and the appropriate amount of time is at least days, and probably weeks, to get a good look at that problem. It might be months.

Susan: That might actually be the biggest pitfall in deep learning, is the assumption that it'll only be a day or two.

Scott: Yeah. Yeah. A day or two minimum. That happens frequently.

Susan: Oh, that's no problem. I'll have something in a week.

Scott: Yeah, "Oh weird. It's not doing what I thought it would do. But what if I just do this little trick?" Two days later: "Huh, okay," and then eight days later, "Huh."

Susan: It's a big time thing, that's for sure.

If you have any feedback about this post, or anything else around Deepgram, we'd love to hear from you. Please let us know in our GitHub discussions .

More with these tags:

Share your feedback

Was this article useful or interesting to you?

Thank you!

We appreciate your response.