Text Cleaning for ASR: The Case of Turkish

August 30, 2022 in Linguistics

Since Turkey is celebrating Victory Day today, and since we've been meaning to write a blog post about text cleaning, we figured we might as well write a post about text cleaning and Turkish! For every automatic speech recognition (ASR) system, cleaning the training data is a crucial part. Speech recognition systems learn how to map speech to its written counterpart by learning speech-text pairs. If the data that teaches it how to do this is messy, the system just won't work well. In this post, we'll explain what text cleaning is, how it works, and why it's so important for ASR. Let's look!

What is Text Cleaning?

Simply put, text cleaning (also called text normalization) is a component of natural language processing that takes raw data and neatens it up, usually in order to use it for something like machine learning model training. While preparing our training data, we'd like the transcriptions to match the spoken phoneme sequences as much as possible. For example, if we hear the words "J. Lo" in the speech file, we'd like its transcription to be "J. Lo" as well. However, if the speech file includes the words "Jennifer Lopez", we wouldn't want the transcription to be "J. Lo"; we'd want it to be "Jennifer Lopez". Although "Jennifer Lopez" and "J. Lo" represent the same entity in the real world, phonetically they don't match at all. The former word is represented by the sequence of phonemes

JH EH N AH F ER . L OW P EH Z

where the latter word sequence maps to a much shorter phoneme sequence

JH EY . L OW

All of this logic also applies to numbers, abbreviations, email addresses-i.e., nonstandard tokens, where we can end up with written text that doesn't necessarily match the pronunciation, need to match up to what's actually being said, and not the real-world entity.

Why Text Cleaning is So Important

There's an old saying in data science: garbage in, garbage out. This means that if you train a model with bad data, your model isn't going to be very good. We want to make sure we have a good match between the phonetics-the actual speech sounds produced-and the phonetic transcription of that speech.

This is the first step in getting an accurate, readable transcript at the end of the transcription process. This is why text cleaning is so important for ASR training. By doing text cleaning before training, you give your model the best possibility of producing what you want. Let's take a look at an example of how text cleaning actually works.

How Text Cleaning Works

Text cleaning is language-dependent. This is because abbreviations, shortenings, and other special text forms have a language-unique relationship to their spoken tongue. For example, "lb" and its relationship to "pound" in English isn't at all obvious if you didn't already know about it, and isn't relevant to any other language. To apply text cleaning to training data, we need a multi-step processing pipeline. Each step transforms the text into a "cleaner" variation of the original.

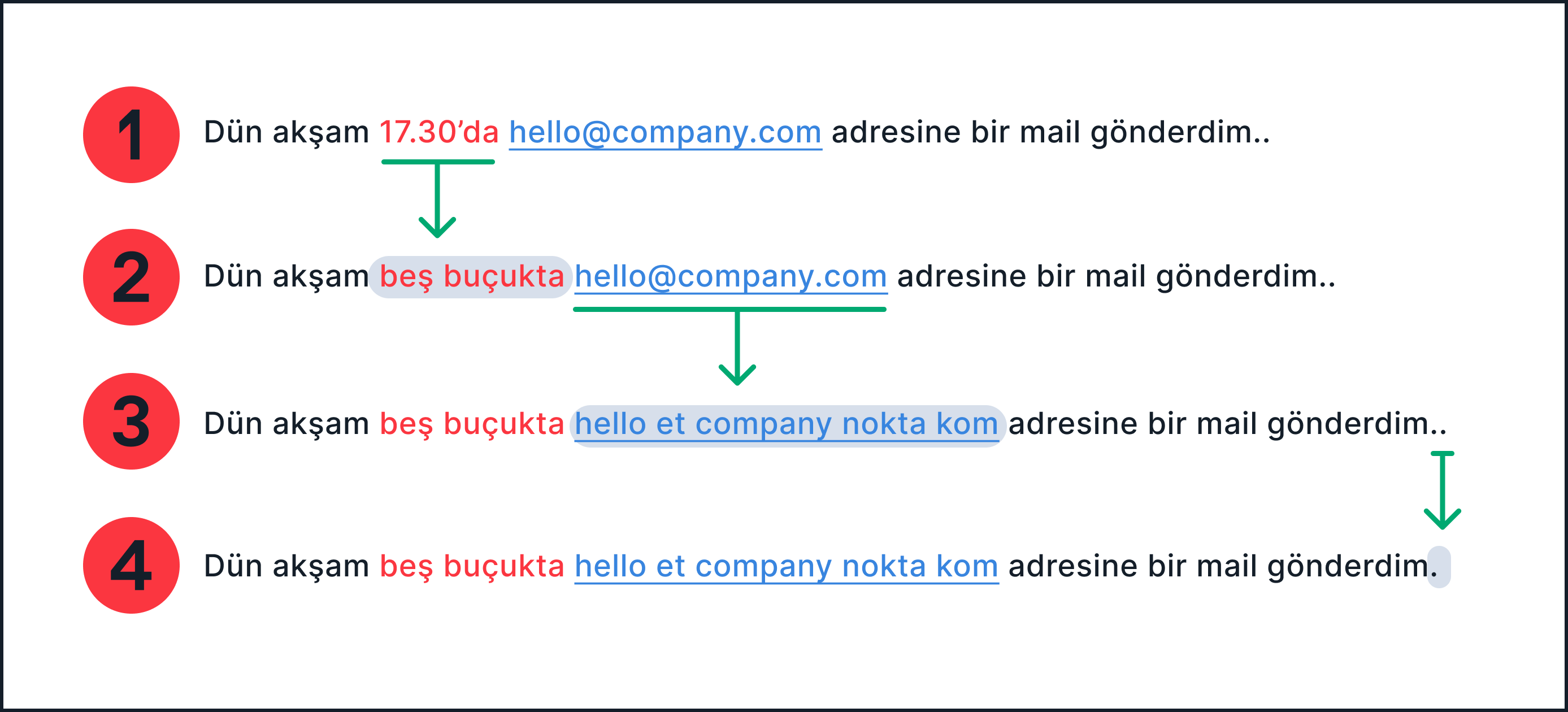

By "cleaner" here we mean "closer to the actual phonetics of what was said". Take a look at Figure 1, below. There you can see an example sentence which is transformed, step by step, into a "cleanest" final version. It starts in the usual written form in Step 1, but that doesn't accurately represent the phonetics of what's being said, so we need to clean it up if we want to use it for model training. In Step 2, we spell out the numbers into words, rather than numerals. And in Step 3, we spell out the components of an email* (which, when said, is a string of words, just as it is in English-"duygu at deepgram dot com"). In the final step, Step 4, we remove the double period typo so that the sentence has standard punctuation.

Figure 1. Text cleaning for the Turkish sentence "I sent an email to the email address hello@company.com yesterday."

Challenges for Turkish Text Cleaning

In the above example, we mostly saw things that would also make sense in other languages-like reformatting an email address into words. But there are unique text cleaning challenges for each and every spoken language, and Turkish is no exception. Let's consider a few, Turkish-specific examples.

The Turkish Apostrophe

One challenge that's specific to Turkish, and which we saw an example of in Figure 1 above, is with the use of the apostrophe. The apostrophe is used often in written Turkish, and is used for separating inflectional suffixes from the proper nouns, numbers, and abbreviations that they're attached to. We need to keep an eye on this when we do text cleaning because some of the changes that we make to the text will also influence whether or not we need to get rid of the apostrophe. For example, when we turn a numeral into a common noun (that is, we turn 3 into üç) we no longer need the apostrophe after we spell it out as text. In the above example, we saw the token 17.30'da became beş buçukta and not beş buçuk'ta; we omitted the apostrophe in order to keep the grammaticality. However, proper nouns will still stay as proper nouns, no matter what text cleaning we do, so they should never lose an apostrophe. But what if our proper noun has a number in it? In Figure 2 below, the apostrophe is used to separate a proper noun from an inflectional suffix, and hence a good question arises: should we keep the apostrophe or not?

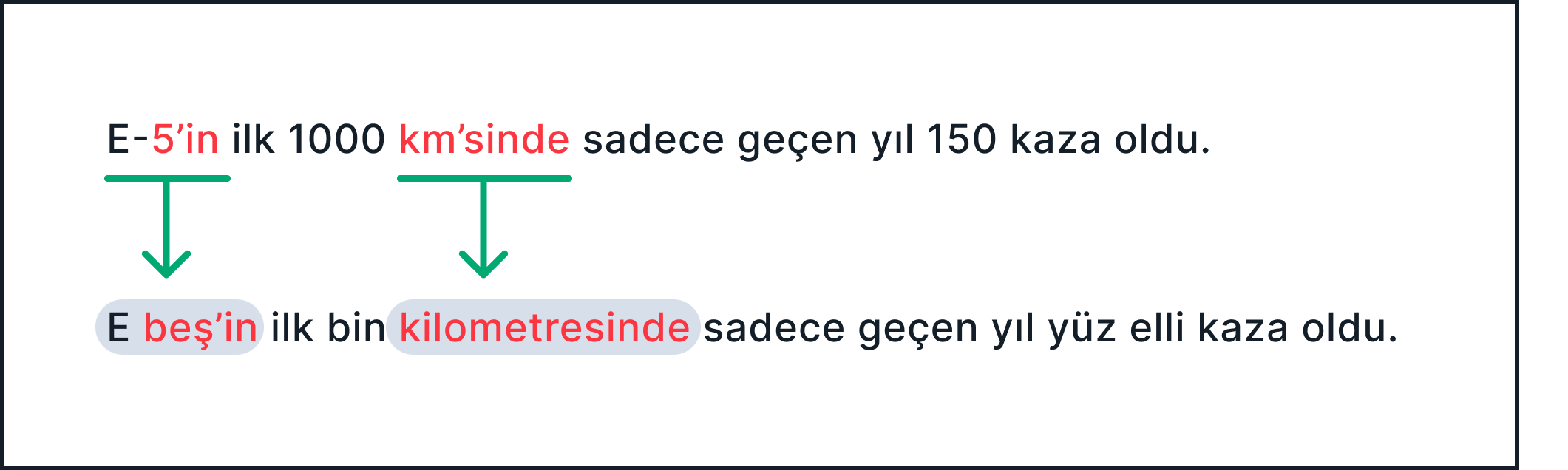

Figure 2. Example of a possible text cleaning for the Turkish sentence "150 accidents happened in the first 1000 km of the road E-5."

In Figure 2, we deleted the second apostrophe safely. However, keeping the first apostrophe creates a not-very-good looking token: beş'in (which should be beşin according to Turkish orthography). Here, 5 is part of an entity-the name of a road-and also a number itself. On the other hand, beş 'five' is just an ordinary noun and beş'in is an ordinary noun with an apostrophe (which is not quite grammatical). So what's the solution here? It totally depends on the model vocabulary of the ASR model that one wants to use. Here, it's indeed better to keep E-5 intact and not normalize the 5 to beş because it's part of an entity. Hence, the final cleaning result should look like this:

E-5'in ilk bin kilometresinde sadece geçen yıl yüz elli kaza oldu. 150 accidents happened in the first 1000 km of the road E-5.

Long story short, we need to pay attention to apostrophes to do text cleaning in Turkish correctly. Sometimes we delete them, sometimes we keep them; the important part is to get grammatically correct sentences even after the cleaning and to do so consistently.

Another Apostrophe Challenge

Because the apostrophe comes hand in hand with inflectional and derivational suffixes, we also have to pay attention to phonological processes such as consonant assimilation and vowel harmony rules. Let's look at what those terms mean, and an example of each. Consonant assimilation refers to two consonants becoming more similar to each other when they occur next to each other. We can see an easy example of this in English with the words cat and dog. When we add the plural -s to these words, we pronounce them differently based on the final sound: like an /s/ in cats but like a /z/ in dogs. (This is specifically an example of voicing assimilation if you're curious.)

This consonant assimilation in English is pronounced but not written. Modern Turkish writing, however, does reflect consonant assimilation when it occurs. And when it comes to consonant assimilation in Turkish, we're actually sort of lucky because even if consonant assimilation occurs with a suffix, the apostrophe is still used.

Dün saat 3'te beni görmeye geldi. He came to visit me yesterday at 3PM.

In this example, the first consonant of the suffix /-dA/** has assimilated and become /te/ after üç 'three', so we don't need to do any extra processing after deleting the apostrophe in this case. So far so good, but now let's look at a trickier case with a derivational suffix and abbreviation combo, along with a typo. One of the main issues that comes up with text cleaning is that you often can't assume that your input text follows the normal rules of grammar and orthography, so you have to do some checking.

Yrd doçluk sınavı kalkmış. Yrd doç luk sınavı kalkmış. The entrance exam for assistant professorship is canceled.

In both sentences, the words yrd and doç are abbreviations. Yrd is short for yardımcı 'assistant' and doç is short doçent 'professor', so yrd doç is a bit like asst prof. Here, there are no apostrophes between doç and luk at all to indicate a suffix is appended to an abbreviation. In the first sentence, the spelling doçluk is not great grammatically but still acceptable, while in the second sentence, the two words doç and luk should not be written separately. In perfect written Turkish, they should be written together, but with an apostrophe, like this: Yrd doç'luk sınavı kalkmış. Figuring out what is going on with either of the two original sentences could be difficult, but fortunately we have a hint-luk is not a Turkish word; however, it is a suffix. And, what's more, it is following the rules of Turkish vowel harmony here, as it harmonizes with the vowel of the previous word doç. Vowel harmony, very briefly, is a process that forces all of the vowels in a word to be part of the same set. Because /u/ and /o/ are part of the same set, we can conclude the second sentence is a misspelling and we can correct this mistake by deleting the space in between to get a "cleaner" version: Yrd doçluk sınavı kalkmış.

Processing Currencies in Turkish

Phew, that was a lot! The good news is, we can relax a bit when processing some other types of tokens, though; processing currency symbols, for example, is quite easy. Unlike English, in Turkish we don't append a plural suffix to currencies whose value is more than 1. Please compare:

Hence, a simple piece of code is enough to clean up currencies. We first parse out the currency symbols with a tiny regex, look them up from a predefined dictionary of currency words, and finally replace them in the text. The code for this is below in Figure 3.

import re

CURR_SYMS = {

"$": "dolar",

"€": "euro",

"£": "sterlin",

"¥": "yen",

"tl": "lira",

"ytl": "lira",

"₺": "lira"

}

CURR_REGEX = r"([$€£¥₺]|y?tl|try)"

def convert_currency_syms(token):

token = token.lower()

words = CURR_SYMS.get(token, token)

return words

def clean_currency_symbols(sentence):

match = re.search(CURR_REGEX, sentence)

while match:

mstring = match.group()

mstart, mend = match.span()

sentence = sentence[:mstart] + " " + convert_currency_syms(mstring) + sentence[mend:]

match = re.search(CURR_REGEX, sentence)

return sentence

sent = "Hepsine 100$ verdim."

>> clean_currency_symbols(sent)

"Hepsine 100 dolar verdim."Figure 3. A sample code for running a regex to get correct Turkish currencies.

We literally did nothing to currency words; no plural suffix or any other suffixes were added by us. If we were processing English, though, we would need to parse the currency symbol together with the number to check if the number is 1 or not; if it's not 1, we need to add a plural suffix to the currency word. Please note that the code segment in Figure 3 shows only one step of processing, that related to processing the currency symbols. As we mentioned previously, all conversions are done in individual steps, hence the number 100 would be processed in a separate number-cleaning step.

Text Cleaning for Numbers

Numbers can introduce other challenges as well. For example, converting ordinal cardinal and decimal number tokens into words; as well as converting times, dates, telephone numbers, postal codes, and other sorts of number tokens into words. Parsing number-type tokens can be tricky; numbers come in different shapes. There are decimal numbers (which include commas), big numbers (which include periods), phone numbers (including parenthesis, dashes, plus signs, and even more), postal codes (address strings should be extracted first to spot them), and so on.

Cleaning numbers is challenging for each language indeed. Quite a number of regexes and other sorts of parsers (including NER and CF parsers) are used. For an example, this regex should parse out big numbers (such as 1,250,000) in English text: \b\d{1,3}(,\d{3})+\b Big numbers are written similarly in Turkish, but with a period instead of comma; hence, a tiny modification to this regex would suffice: \b\d{1,3}([.]\d{3})+\b It's totally expected, when we're building text cleaning pipelines, that we implement both language-specific and some "universal" cleaning methods. For each language we process, we find common token types and processing methods, but at the same time, we implement quite a lot of language specific text cleaning methods as well.

Newsletter

Get Deepgram news and product updates

Wrapping Up

When it comes down to it, all languages are beautiful and yet challenging at the same time; dealing with natural language is never easy. At Deepgram, we all enjoy working with speech and text, and we embrace both the difficulty and the beauty of natural language. We hope you enjoyed this article and share our joy for Turkish, too! Please join us for more content on our blog and follow us on LinkedIn.

And, if you'd like to give Deepgram a try for yourself, sign up for Console for free and get $150 in free credits to give it a try.

* Of course, sometimes we might want an email to appear in a final transcript. In that case, we can do a bit of postprocessing to the model output to get the final transcription in order to reverse normalize ...-at-...-dot-com word sequences into a single email token. But for the purposes of this post, because we're looking at the phonetic level, we'll want to represent the pronunciation rather than what we want the final output to look like.

** The /d/ becomes /t/ due to assimilation with the preceding sound, and the A represents a vowel that changes depending on vowel harmony, which in this word, becomes /e/. Thus, we end up with /te/ for the suffix.

If you have any feedback about this post, or anything else around Deepgram, we'd love to hear from you. Please let us know in our GitHub discussions .

More with these tags:

Share your feedback

Was this article useful or interesting to you?

Thank you!

We appreciate your response.